When I was growing up, my family moved frequently. My dad worked for the phone company, working his way up from technician to communications director, and he was called to different parts of the province as new offices opened up with the expansion of telecom services throughout the 70’s and 80’s. We moved as his career moved, every few years, adapting to new towns, new neighborhoods, new schools, new houses. This pattern persisted into my adulthood, as I bounced from college to college to Europe and then back to college and myriad apartments across those journeys; even once Kyle and I were married and I was settled into grad school, we moved multiple times, bribing friends with beer and pizza to schlepp boxes and desks across town.1 I can’t even count how many times I’ve moved; the criteria for accounting slips as I tick places off on my fingers. Do I count couch-surfing that one summer in Spain? The two months with the terrible roommate in a tiny heritage studio in downtown Vancouver (an arrangement that ended abruptly when she moved a homeless guy into our one shared closet)? The four months on Roncesvalles Avenue in Toronto, above the Polish bar that was relentless about playing polka music with the bass cranked until 2 in the morning? The stretch of time living with my mom when I came back from Europe, jobless and homeless with a broken heart?

Moving was just part of life. There was a kind of comfort in it; as I got older, I never worried about whether any one place suited all of my needs, because it didn’t need to. If I became unhappy with a place for any reason — or even just bored — I could always move. Change is exciting. New landscapes are fun to explore. Decorating new rooms is more interesting than redecorating old rooms.

Anyway. I liked moving. We liked moving. We got pretty good at it.

When we moved to Los Angeles from New York in 2013, we figured that the pattern would continue: we’d stay a couple of years and then move on, probably back to Canada. We were moving at the behest of Disney, who provided such luxuries as a relocation consultant, high-end professional movers, and a post-move organization consultant.2 Easy-peasy. We rented a nice house with a pool and an orange tree from a nice older ex-pat Canadian lady and settled — such as it were — for a standard tenure, anticipating two, maybe three years at most, three years being the longest that I’d ever live in any one house anywhere, ever, in all of my life.

We ended up staying eleven years. Eleven years, almost to the day.

Eleven years in one place is more than enough time to lose your muscle memory for moving. It’s also a lot of time in which to accumulate more stuff, especially when those years are prime parenting years and your lives are a hurricane of school papers and artwork and crafts3 and endless cycles of new clothes and bedroom posters and assorted accoutrements related to changing tastes in bedroom decor (the child to tween to teen design arc is a very sharp and steep curve.) When we first got the news, the initial oh-shit gut punch was tempered, very slightly, by the smallest tinge of excitement: we will go somewhere new! And then the force of the punch landed: we need to go somewhere new. With all of this… stuff.

I wrote a few weeks ago about the weight of the loss of the house that we lived in for eleven years. I’ll probably write about it again. The other week, I — determined to convince everyone in the household that This Is All Fine — told Jasper for the umpteenth time that I had moved nine times by the time that I was his age. Nine times! I didn’t have a single childhood home; I had many! I moved all the time! It was great! It made me who I am. He very patiently reminded me that I was forgetting an important fact: that he is not me. I have a childhood home, Mom, he said. This one. Oof.

Saying goodbye to a childhood home is hard. That holds even when the childhood wasn’t your own. I am saying goodbye to the home that I made with my children. I am saying goodbye to their childhoods, and they are saying goodbye to their childhoods, and that is hard.

What is also hard: moving eleven years of family life from a four bed plus garage home to a three bed minus garage home, when your moving muscles have atrophied and you’re on a strict budget and you’re determined to DIY the whole thing. No relocation consultant, no professional movers, no organizational advisor — just us, a truck, and the occasional extra muscle from Kyle’s man friends. Complicating the matter was the fact that we had committed to also doing the work of clearing out the house that we were moving into (a story in itself), emptying it of its decades of accumulated life to make space for our own. We were moving two houses,4 on our own, while burdened with an entirely fucked-up false moving consciousness that had us convinced, very wrongly, that It Was All Fine and also No Problem At All, We Got This. In a heat wave.

It was not at all fine. At no point at all did we ‘have that.’ There were a million problems, of which I will spare you the details. We had one blessing: that our landlord felt sufficiently bad about selling that he gave us extra time to move out. When he offered it we were convinced that it wouldn’t be necessary; we were wrong. It took us fully seven additional days — well into the night of the seventh, actually, with a morning run back on the eighth — to get everything out of the house. Fully half of it is currently sitting outside the new house, partly in the carport and partly in the drive, which is thankfully very long and sufficiently private such that our general Beverly Hillbillies vibe is mostly not fully visible from the road.

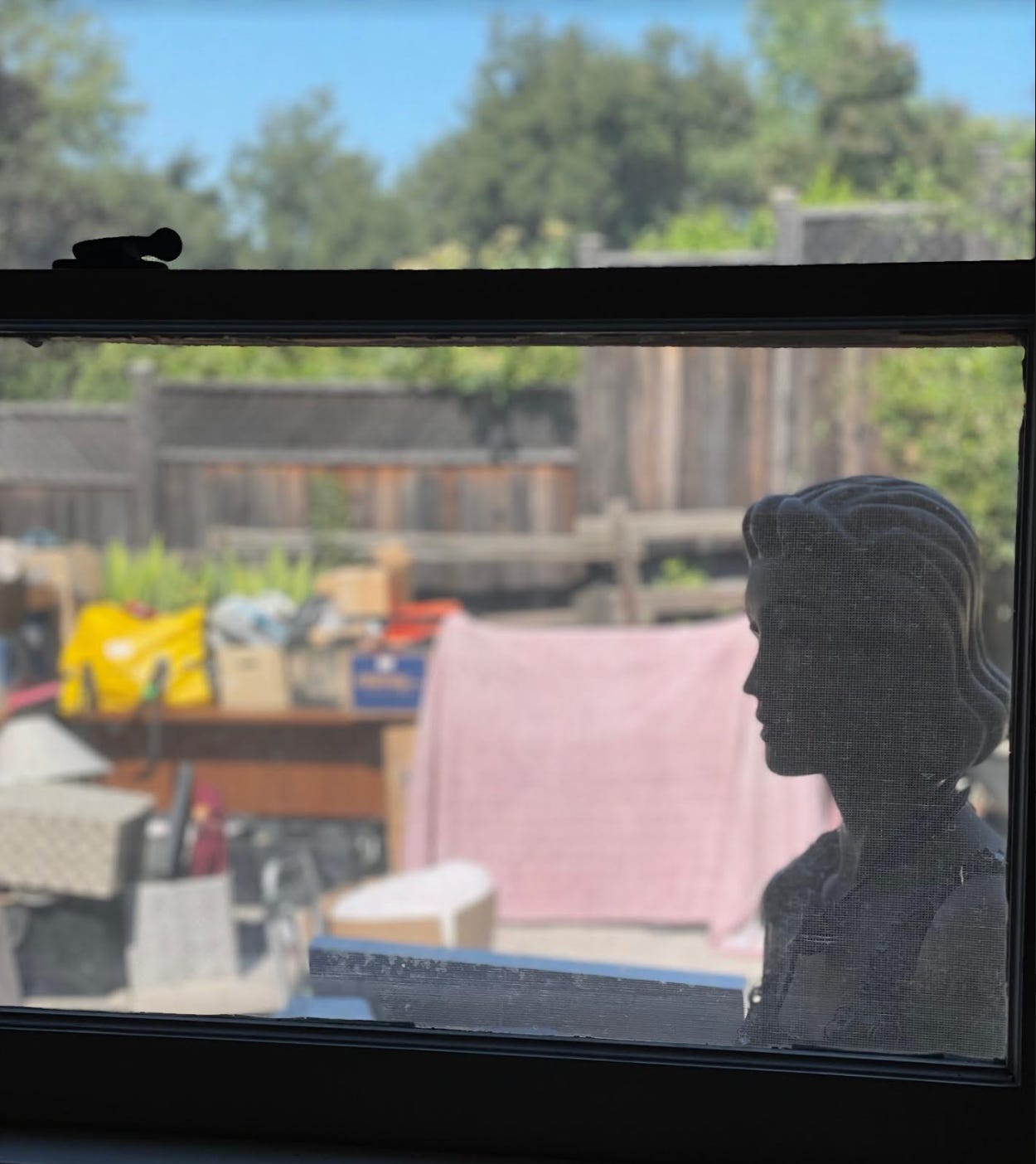

I am dead. I am completely, totally dead in a way that can of course only be figurative while also being 100% TRUE FACTS because how else can you describe what it feels like to have fully hit your physical, emotional, and spiritual limits and then passed into a purgatorial state in which you cannot think or feel and wherein you have a vintage mannequin standing amidst mountains of boxes full of your entire life, judging you. I am utterly defeated, done, down, deceased.

But I am also, in some strange, possibly perverse way, grateful for how this has played out. If we had to move for the first time in over a decade, from our home of eleven years, from my children’s childhood home, from the place of our longest-standing state of security, from our comfortable state of fixedness… then I am glad that it was hard, slow, challenging work. I am glad that it was labor, in the fullest sense; I am glad that we experienced all of the pains that come with shifting a life from one place to another. I am glad that we did this work ourselves, that we are still doing this work ourselves, as absolutely grueling as it is, because in doing the work ourselves we are forced to confront the bearable heaviness of our being; we are compelled to lift and bear and move the full weight of our beautiful, complicated lives.

When my mom died last year, it was after weeks in the hospital, weeks in which I stayed steadfastly by her side, day and night, adjusting bed settings and getting blankets and fetching water and mediating with nurses and holding her hand. I was exhausted and lonely and terrified but also deeply, deeply grateful to be there, grateful to be able to do the work, grateful to have that time of laboring toward a transition that we hoped would be to new life. That the transition turned out to be death makes that labor all the sweeter, in retrospect: that labor held me and compelled to be fully there, deeply engaged and attentive and in the moment, in the series of moments that would be our last. It gave me time with her, of course, but it also gave me the consolation of effort: the reassurance that I’d been fully present to the moment, with every physical, emotional, and spiritual muscle alive to the work of being alive, with her, for that time. So it has been with this move, I think: an exercise in the work of being alive, in working with the movements of life, in moving with intention and attention, alert to the pains and frictions and frustrations and knowing that they’re just part of it all, this whole life thing.

So if I’m dead, it’s an earned death, and one from which I’ll recover. And then, I’ll just keep moving.

We even did this after we bought our first home, in Toronto, the thing that everyone says that you’re not supposed to do with real estate: we decided our little semi-detached house was too small, and sold it in just under three years, moving to a bigger house a little further out just to sell again a few years later when we moved to New York. (That first house is now worth about 8 times what we paid for it. Would I have wanted to stay put if I had known? Nah. This may be why I have never accumulated real wealth.)

Declined, because really? I couldn’t imagine someone sorting through all of our stuff and making sense of it. That’s the kind of work you do yourself, because stuff-sensemaking is so, I don’t know, personal. Also, embarrassing.

Now, of course, I would take that offer in an instant. Exhaustion erases shame.

Including one collection of hand-written recipes by Emilia, of which I have no memory, but which has obviously gone immediately into the cookbook collection, which has grown significantly since the discovery of not just Emilia’s recipes, but at least three extra boxes of cookbooks that were never even unpacked when we moved from New York eleven years ago.

Three, actually — we also had to move Emilia from her college residence to a new shared house, in Santa Barbara, which is two hours away. This was during what was supposed to be the last week of moving out of our original house, which was not the last week, because we grossly underestimated the effort that this would all take.