I spent the weekend deep in my feelings about an anglerfish. I wept, I lamented, I reposted maudlin Threads about dying things seeking light. I do not ordinarily get emotional about fish,1 and this was a fish that I didn’t even know personally. I didn’t know much about this particular fish at all, save that she emerged from the murky hell-depths of the ocean and swam up to the surface and died. I of course learned more about her as I got more invested in her story, which was all over the Internet because a) humans almost never see anglerfish,2 and b) it was sad.

Here is what I discovered about the anglerfish during my emotional journey tracking her journey:

Smol

Female

Not as scary looking as I had been led to believe about anglerfish

Might have been sick

Might have been escaping a hostile environment

Almost certainly was not, actually, seeking the sun

Very unlikely to have been in search of a whole new world

Had very probably not made a deal with a sea witch

Died almost immediately upon reaching the surface

Was relatable as f*ck

I was not alone in being sad about the anglerfish. A not insignificant share of the Internet was also all up in its collective feelings about the anglerfish, and was coping by making memes and TikTok videos, which I found reassuring. That little hashtaggable anglerfish meant something to all of us. We were holding hands on an emotional journey.3 It didn’t take long for the naysayers to come out, of course; this was to be expected, because there’s nothing that the mansplainier parts of the Internet like to do more than explain to people why they’re wrong. That anglerfish was not seeking light! There was nothing poetic about her death! Stop anthropomorphizing, losers.

There’s a level at which I totally get this response: there are far greater horrors in the world than dying anglerfish, and it’s very possible if not likely that some of those horrors (climate-related) have something to do with her death. We should absolutely be in our feelings about those horrors, and we should probably be creating more Internet content about them. And yes, we should be as moved and catalyzed by science as we are by vibes. What good are vibes when the world is burning?

But here’s the thing about vibes: they’re the abstractions of our feelings, they’re the energy of poetry and of music and of story, and they’re not at all at odds with science or reason or being clear-eyed about apocalypses. In fact, I’d argue that vibes, via story, art, music, poetry, etc., are essential to our ability to engage with things like science and reason and logic and the like, and to our ability to survive apocalypses.

There’s a reason that so much learning happens through story and art and music and poetry, because story and art and music and poetry activate empathy, and empathy opens not just our hearts, but our minds. It expands the horizons of our moral imaginations. It powers our ability to see beyond ourselves, which we must do if we are to be able to think and dream and ideate beyond the limits of our own isolated experience. It unlocks our capacity to imagine and connect with the experiences of others — all others, including anglerfish.

How radical to empathize with an anglerfish! A creature that we’ve long thought of as terrifically ugly, even horrifying, a monster from the deep, a thing (we absolutely tend to regard monsters as unsouled things) that should defy empathy suddenly becomes the focus of our care, and that’s pretty extraordinary. This being from our nightmares swims into our imaginations in a beam of light, and instead of recoiling, we reconsider it. We see that it is small, and vulnerable. It’s still got sharp teeth, but in the filtered underwater light, those teeth become thread-like protrusions of vulnerable, breakable bone, and it seems so fragile and so somehow, while swimming upward to the sun, “it” becomes “she” and gets a little closer to us, or us to her. We start to see her, a delicate creature of nature, and we start to see ourselves in her, and we imagine that she — like we — must be a being of light who can’t help but be drawn to the sun.

By giving her an identity, we ensoul her. That ensoulment is necessary for (a precondition to? Which comes first, the ensoulment or the empathy?) our ability to empathize with her. And the more we empathize, the less monstrous, the less alien, the less ‘other’ she becomes. The more her story world expands to reach ours, the more that we can see ourselves within it.

What we see there: a world full of darkness and shadow and light, and an ensouled being, moving towards light. Why she moves in that direction doesn’t entirely matter; the mystery of her movements opens space on that landscape for us to apply our own stories as maps for meaning-making, and brings us closer to her. We see that she carries her own light, which feels significant: do we not carry our own light? Why do beings with their own light sources go out into the sun, or gaze at the moon and stars? What drives us from our safe havens toward brighter open spaces? Are we all just journeying out from underworlds that we don’t recognize as such? What light yonder?

We summon metaphors of moths and sunflowers; we tell stories about Icarus and Raven. We suspect that any living thing that loves warmth and light must have a soul, or at least a spirit, for reasons that none of us can fully articulate. We turn our golden faces into the sun. Any being that turns to the sun, to the light, must be like us, we think. We know this at the level of our bodies. We feel this in our bones, our veins, our cells.

We like things that are like us. They don’t have to look like us, but they have to have the semblance of a soul. We don’t know what that means exactly, but we think that we know it when we see it, or the possibility of it. We cry at Pixar movies because we believe, somewhere deep down, that toys and lamps and clownfish and robots and bao buns could have souls; that belief brings them alive for us, and not just in the sense of liberating them from the confines of the page or screen. Like clapping for Tinkerbell, we bring them to spiritual life. When we believe that something that is not us has a soul, we activate their spirit with our imagination.4 And when we do that, we create an imaginative landscape upon which other beings have souls and that imaginative landscape is very much alive and important because anytime we’re on it, we are forced to keep our minds and our hearts open to the possibility that life, the universe, and everything are bigger and more complex than we could possibly understand. And that maybe, just maybe, we could love everything that’s there.

The Disney version of the story The Little Mermaid gets criticized for what many interpret as the sexist message driving the story: that the heroine, the titular little mermaid, Ariel, gives up her voice — and her home and her family — for a boy. What such critiques usually overlook is that Ariel feels the pull of adventure long before she ever sees the boy. She longs for a whole new world because of course she does: it is fully and richly human to chafe against being held in place, to want to follow our curiosity and discover new things, to look toward the horizon and wonder what’s there, to consider risking everything just to see it for yourself. That love becomes the catalyst for the mermaid’s exploration — the thing that gets her off her tail and into bargains with sea witches in order to make the journey possible — just maps to what has been true for women and girls across all of history and most cultures: you usually don’t get to leave home for any reason but the one that connects you to a man. It’s why we don’t see many journey stories for women and girls: the only feminine journey is the one that takes you out of one home and into another. If that journey actually involves a love that you choose for yourself… well, that’s a radically liberatory thing. And liberation is the kind of thing that many beings will risk everything for.

In the Disney story, of course, Ariel’s risk pays off and she lives happily ever after with her legs and her voice and her prince. In older versions of the story, she is turned into seafoam and dies. For many, those tales would read as cautionary: if you leave home and family, little lady, you’ll probably die. For some, those tales would read as a dare: you could die, but also, you could be free. For a few, an inner voice would whisper: it would be worth it.

There’s no flight from home or pursuit of romance in the anglerfish’s story (that we know of), but it’s still a very gendered story. I don’t even know if we know the sex of the anglerfish, and I’m not going to look it up because it doesn’t matter: the Internet gendered her and that has shaped her mythos in so many ways.5 The gender assigned to her serves to underscore her vulnerability, of course, which deepens the pathos of the story. We love a small damsel confronted by a distressing world: a princess surrounded by dragons, a demi-goddess in the clutches of Hades, a mermaid indebted to a sea witch. We root for them to be saved; sometimes we even root for them to save themselves.

It’s still gendered even when our heroine is not a princess, but a monster. Our heroine emerged from a dark underworld, a terrifying being from the depths who became something close to beautiful in the glimmering light of the water-filtered sun. This, I think, is where she most deeply triggered our empathy, or at least the empathy of those of us who have ever felt trapped in the murk and dark of our own bodies. She is every female-coded being who has ever lurked in the darkness of her own culturally-imposed shadows, convinced of her own monstrousness, cleaving to her own small light, wondering if anything would be different — if she would be different — in other waters. She is every she or them or we who ever dreamed of escaping from an underworld and going in search what might be found outside, no matter the danger. This is where folklore meets National Geographic, and where our anglerfish becomes not just text, but poetry: she becomes a little mermaid for our own dark time, propelling herself toward a brighter light, knowing that the journey might kill her.

There is of course no lack of pathos in what is likely the real story: that the anglerfish’s habitat became toxic due to ocean warming from climate change, which caused the anglerfish to become sick or disoriented and therefore end up in foreign waters. There’s no heroine’s journey in that narrative, but it still doesn’t preclude stretching our imaginations and our empathy. If our anglerfish is just an un-ensouled casualty of climate change, what then? Does it really serve us to look at the poetic possibilities of the anglerfish and say, no, ditch the poetry, better to distance ourselves and not identify in any way with what might have happened? Until relatively recently in human history we were live vivisecting dogs for science, telling ourselves that their cries of pain were akin to the pinging of wires in machines, because dogs couldn’t possibly feel pain, because dogs couldn’t possibly have consciousness, never mind souls. We still do terrible things to animals — we do truly terrible things to other humans — on the basis that they’re different enough from us to not matter, to not count, to not warrant empathy.

We don’t care about anything that we can’t write a poem about. And when we stop poetry, we stop caring.

When we strip anything of poetic possibility, when we deny poetry for or about other beings or the world or ourselves, we expand the space of difference between us and within us. We widen the space of difference to a fucking gulf, an uncrossable chasm, and in the space of that chasm we become the horrors. We become unsouled, in practice at least.

But we can bridge, even fill, that chasm with poetry — with art, with music, with story, with love. To treat anything as a worthy subject of poetry is, again, to ensoul that thing; it is to accord that thing beingness and to recognize it as a being, as a part of being. It’s to transform the moth or the sunflower or the anglerfish from thing to being, and to introduce the possibility of identifying with their being, perhaps even to loving their being. To go from it to them, from other to our own.

This all sloppy theology and even sloppier philosophy, I know. But still. We need poetry about that anglerfish in the same way and for the same reasons as we need any and all art: because if we can’t imagine the soul of an anglerfish and weave that imagining into story, we can’t really do it for anything. And if we can’t do that, we’re lost.

I saw someone post on Threads, responding to criticism about being poetic about the anglerfish, “here I am, being poetic as fuck among the Horrors”6 and I thought, this, this is whole point. This is what we must do, all of us, if we’re to survive, and maybe thrive. Be poetic as fuck among the horrors.

Be poetic as fuck among the horrors.

If that means crying for the beautiful little mermaid heroine anglerfish, so be it. I’ll share my tissues.

(Links to Threads)7

If my mom were alive to read this, she would chastise me and accuse me of telling lies, because when I was in college I wrote a short story from the point of view of a fish being caught on a hook and dying, and being a vegetarian asshole, gave it to her, a fly fisherwoman, in order to make the point that fish have feelings and that I cared about those feelings and therefore that hurting fish hurt me. She is no doubt doing this from whatever realm she is in.

Also, I’m crying about literally everything these days, so this particularly emotional dive is in no small part due to being, you know, tender, but I’m actually really passionate about this stupid anglerfish so down the rabbit hole (octopus hole? leviathan trench?) we go.

They live so deep down in the ocean that they’re rarely even caught on video; most of us only know them from that terrifying scene in Finding Nemo.

That some were making Pixar-style shorts about the anglerfish on TikTok just intensified the journey, but I think that we were all here for it.

There’s a chicken and egg question here — which comes first, the soul or the belief in the soul? — that I already referenced above and that I am not equipped to answer. I am aware that I am indulging in some sloppy, ad hoc theology. It is what it is; I am, after all, just telling you stories.

POST-PUB EDIT. Sorry, couldn’t help myself; I had to investigate. We know that this anglerfish was female because only female anglerfish have bioluminescence.

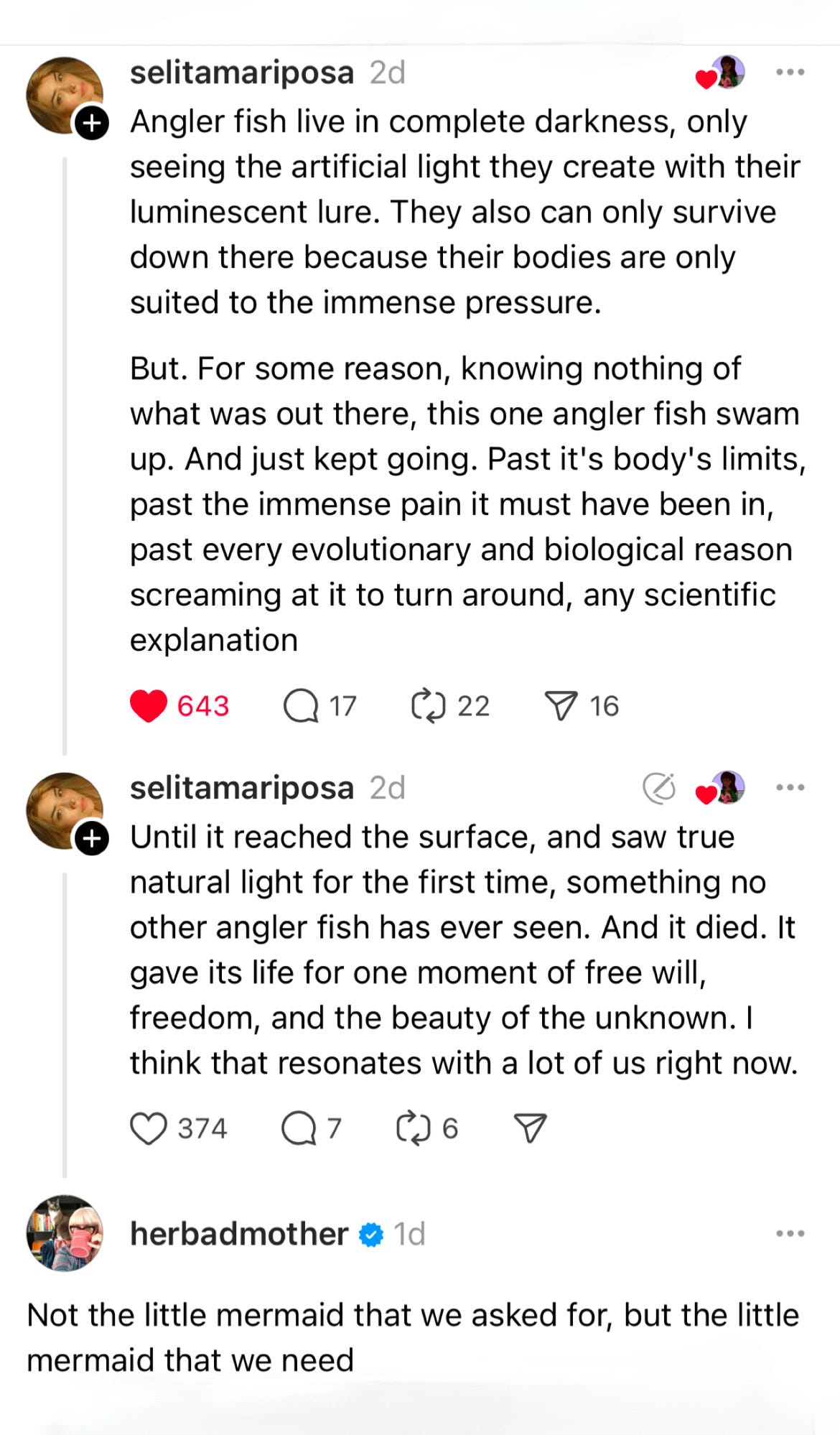

Original thread in image above started by @theeblackdahria_ with response by @selitamariposa

Since I’m being more careful than normal about my internet scrolling for self-protective reasons right now, I completely missed this entire story about the she-monster fish! Thank you for such a thorough retelling and exploration. I love the Little Mermaid bits, and I concur that we need more of all the good stuff (poetry, art, etc) now more than ever!

I knew nothing about the anglerfish and now I am invested! This little Icarus fish deserved this ode.